A COLLECTION WITH 3 THRUSTS

ART, HISTORY AND TECHNIQUE

HISTORY

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: ITS ORIGIN

It all started in the Bronze Age, when peoples who had settled down began to focus on developing luxury tools and comfort items: the art of stone, ceramics and metalworking. Some five thousand years ago, by chance and through the vagaries of fire, they discovered that certain mineral compositions could vitrify, and they used these shiny and impermeable glazes as a coating for stone objects and pottery.

And then, in the middle of the third millennium BC, we see the emergence of the first objects made entirely from glass, in a culturally advanced region, Mesopotamia (Iraq/northern Syria). Very few remnants have come down to us before this art really began to develop in the 15th century BC, which sees the appearance of the first vessels, produced using rudimentary moulding techniques. Polychrome is achieved by making glass mosaic.

Vestiges

Almost ten centuries of the history of glass can be summed up by small objects: beads, amulets, cylindrical seals and so on, moulded or shaped using rudimentary methods and finished off with stone sculpting tools.

Lacking specific techniques and tools, the arts of working in stone, ceramics and metalworking, which had already been developed to quite a high level of sophistication, play a major role in the development of the procedures of firing, shaping and decoration, and in the birth of forms and styles.

The glass workers of old sought, through their materials and the ways in which they worked them, to imitate precious and semi-precious stones such as turquoise, carnelian and jasper: aside from the parameters due to technical skills and the subsequent conservation of the works, it is therefore no surprise that most of the ancient objects are more or less opaque and richly coloured.

The first vessels

The oldest vessels were fashioned on a spindle, a technique which was developed towards the middle of the 16th century BC, and the one which would be most widely used until the invention of glass blowing in the 1st century BC.

Around a metal stalk, the glassmaker forms a core which corresponds to the interior shape of the piece, and envelops it in hot glass.

The piece cools and is emptied off the spindle, which has become very fragile under the effect of the heat.

This technique was used to make small narrow-necked flasks, all of them with a rough interior surface because of the granular imprint of the core.

Mosaic glass

Towards the middle of the 15th century BC, glassmakers succeeded in producing open shapes (plates, beakers and bowls) using sheets of mosaic glass.

Fragments of coloured opaque glass or segments of multi-coloured canes were assembled on a plate in a rainbow-coloured kind of jigsaw puzzle and sealed using heat.

Glass sheets, when reheated, could then take on the contours of a spindle (beakers) or those of a hollow mould (bowls).

This procedure, rich in potential, subsequently diversified into a number of variations classified under the generic term of mosaic glasses.

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: THE INVENTION OF GLASS BLOWING

The invention of glass blowing towards the middle of the 1st century BC, probably in Syria, marked a real revolution in methods of manufacture and in the range of shapes and decorations.

It became possible to produce larger objects, more quickly; glassmaking intensified and spread very rapidly across all the territories in the Roman Empire.

It thrived in Gallia Belgica and the Rhineland in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. Glass became a more widespread and highly diversified product, being used to make jewellery, objets d’art, table services, lamps, vessels and bottles, mosaic squares and then the first glass windows. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the glassmaking tradition continued both in the West and in the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic world.

The Rhineland

There is evidence of glass being produced in Cologne since the beginning of the modern era. Items are numerous and varied, either naturally green or greeny-blue, or artificially coloured yellow, amber, cobalt blue or manganese violet.

The area achieved mastery over techniques including the application of glass threads when hot, etching, engraving and sculpture.

Other centres of production, such as Bonn and Nijmegen, have been identified in the Rhine region.

The Byzantine Empire

The fame of Byzantine mosaics in the 10th to 13th centuries extended well beyond the borders of the Empire, and led to large-scale exports of glass.

The skills of the Byzantine master glassmakers were praised by the monk Theophilus, who in the first half of the 12th century wrote the treatise De diversis artibus, in which he meticulously describes the process for making coloured glass vessels adorned with enamelled and gilded polychrome décorations.

The Islamic world

As early as the 8th century, the Islamic civilisation, thanks to a more peaceful climate, also came to stand out for its rich output. The quality and variety of the techniques is in every way the equal of Greek and Roman glass.

As the 12th century dawned, glassmaking was thriving, with the major centres being Aleppo, Damascus and Fostat (ancient Cairo); its glassmaking art, focusing on enamelling and gilding, reached Europe in the spoils brought back by the Crusaders.

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: IN SEARCH OF CRYSTAL

The search for a pure, clear and colourless material like rock crystal (a type of quartz) was to be the major preoccupation for Europe’s glassmakers between the 15th and 18th centuries.

The term ‘crystal’ was first used in the 15th century to refer to Venetian soda-lime glass whose purity is essentially due to superior quality raw materials and the use of a bleaching agent, manganese. It then came to describe the potassocalcic material being developed by the Bohemian glassmakers by about 1680.

But none of these types of glass without lead oxide is now considered to be real crystal: CEE standards stipulate that crystal must contain at least 24% lead oxide.

It was developed in England in about 1676, when George Ravenscroft discovered that the addition of litharge, and later, minium, to the mix of raw materials made the melting easier and the glass more stable. This material, which rings when struck, and is heavier and brighter than ordinary glass, would very quickly establish itself in the production of luxury items.

Venetian soda-lime glass

In ancient times, glass was made from a mixture of silica, soda and lime. This is the basis on which the Venetians developed their famous cristallo.

So a whole new aesthetic started to serve the table: elegant elongated shapes, a taste for filigrees and millefiori, extremely thin walls, blown stems and so on.

Venetian glass was acknowledged throughout the Europe of the 16th century as representing the pinnacle of luxury glass; its shapes and decorations and the quality of the material were eagerly imitated. In Belgium, the glassmakers of Antwerp, Hainaut and Liège excelled.

Bohemian potassocalcic glass

To avoid importing soda, mediaeval continental glassmakers chose forest glass, also known as fern glass, based on potassium and calcium, which would later be improved upon by the glassmakers of Bohemia in the late 17th century – at the very time that the English were developing lead crystal.

The Venetian aesthetic which was dominant at the time was coming up against the technical limitations of a glass that was harder to blow and a lot less malleable: glass became heavier, walls thickened, and blown stems were abandoned in favour of solid glass. Faceting and deep wheel engraving, which depended on the thickness and toughness of the material, started to appear.

Crystal luxury article

In the second half of the 18th century, crystal articles began to take on the appearance that is familiar to us today: the decoration was exclusively cut. But Great Britain had already lost its monopoly on this manufacturing process, and many continental glassmakers were bent on synthesising it.

In about 1760-1770, Sébastien Zoude in Namur set up the first crystal works on the continent. This really represented the start of Belgian crystal manufacturing, which, in the following century, with Vonêche, Zoude and Val Saint-Lambert, would become famed the world over.

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: THE 19TH CENTURY

The 19th century was the age of the great fusion between artistic and scientific disciplines, rationalising and pushing the boundaries of glass production.

The exploration and reproduction of styles and skills from the past went hand in hand with a spectacular advance in terms of the performance of the furnaces, the mastery of the firing parameters, the purity and quality of the raw materials, the palette of colours, decorative techniques and the ability to obtain glasses with specific properties.

Buoyed by the wave of bourgeois prosperity, the luxury glass market thrived, while production of windows, mirrors, bottles and flasks developed into a specific activity on an industrial scale.

The first step towards mechanisation, pressed glass made it possible to reproduce a moulded decoration on a mass-production basis.

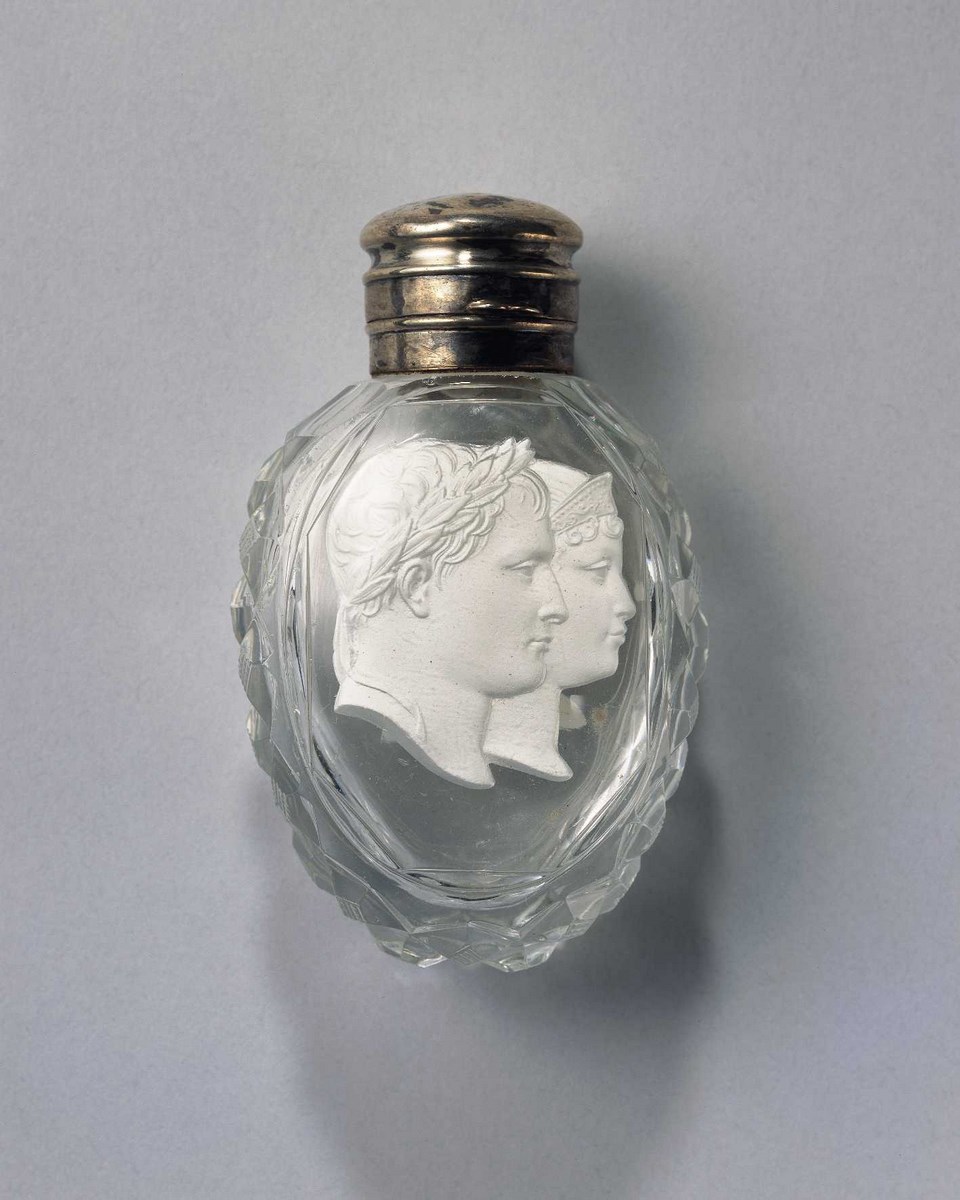

Flask

Blown clear crystal, cut, decoration with inclusion made from white ceramic paste representing on the obverse the heads of Napoleon I laureate and the Empress Marie-Louise wearing a diadem and on the reverse, the young king of Rome. Silver stopper.

Cristalleries de Vonêche, Belgium, circa 1812

Inv. 496

Photo: Paul Louis

Empire style

Empire style characterises the production of the first quarter of the 19th century: clear, cut crystal in sober forms, sometimes mounted in elegant settings of gold, silver or bronze, or wheel-engraved glasses (deep hollow engraving) – a discipline in which the engravers of Germany and Bohemia excelled.

Central Europe

Under the influence of fashions from Central Europe, prominent among them the Biedermeyer style, glass begins in the 1830s to show a strong tendency towards colour, coupled with a taste for heavy, massive shapes with complex cut-out profiles.

At the same time, the French crystal makers launched the fashion for opaline glasses.

The romantic movement

The first major international exhibition, at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, showcased the triumph of coloured glass and the pinnacle of cut crystal, which was about to undergo a quarter-century in the shadows.

Driven by romanticism, copies and pastiches dominated, allowing glassmakers to return to the skills of the past or to explore those of the Orient.

The wind of the aesthetic revival would soon be starting to blow…

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: ART AND INDUSTRY

After having catalogued its rich heritage, glassmaking blended it in an aesthetic with a new lease of life: as from the second half of the 19th century we see new aesthetic trends sneaking in, where the creators place themselves at the service of industry.

These were to converge into an international movement, Art Nouveau, whose protagonists were the likes of Gallé, Daum, Tiffany and Loetz.

With talented creators at its disposal, Val Saint-Lambert embarked on the richest chapter in its existence.

Off to the side, in their respective workshops, the French ceramic engineers Henri Cros and Georges Desprez were developing a fascinating material: pâte de verre was born.

Emile Gallé

Emile Gallé was the giant of Art Nouveau, using a staggering diversity of technical procedures and, through his aesthetic innovations, giving glass its status as an objet d’art and something to be collected.

Alongside mass-produced pieces, in multi-layered glass engraved with acid, Gallé developed his own personal, experimental production, of which this vase is a splendid example.

Val Saint-Lambert and its designers

Within the Val Saint-Lambert design service, talented designers contributed to the great stylistic movements of the late 19th and early 20 centuries.

Frenchmen Eugène and Désiré Muller imposed the ‘school of Nancy’ style launched by Gallé, with their ‘fluograved’ vases, while a more original trend dubbed the ‘van de Velde line’, with its massive vases, lined and ornamented with deep cuts and curves, also developed.

Pâte de verre

As an open window into new artistic possibilities, pâte de verre hardly lends itself to mass production.

It is made of powdered or crushed glass, shaped in a mould and heated until the various components fuse together. However, some crystal manufacturers were taking an interest in it at the beginning of the 20th century: we might mention the fruitful collaboration between Almaric Walter and the Daum crystal factory, and the tests conducted by Adolphe Lecrenier at Val Saint-Lambert, which were never followed up.

In the period between the two world wars, François Décorchemont, Argy-Rousseau and Georges Despret ensured the survival of the pâte de verre technique in some extraordinarily delicate and subtle creations, both one-off pieces and mass produced.

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: GLASS AND ART DECO

In the aftermath of the Great War, Europe would never be the same again. Since the end of the 19th century, major upheavals had been underway; the glass industry was painstakingly making the costly transition from artisanal to industrial production, from pot furnaces to tank furnaces, from mouth blowing to mechanisation.

A constantly evolving environment and increased competition heralded the advent of a difficult future for European glassmaking.

The 1920s saw us stepping boldly into the era of Art Deco and its geometric stylisation, magnificently served by René Lalique, who focused his extraordinary talents on mass-producing pressed glass. In Belgium it was the heyday of Val Saint-Lambert and the Central Region.

Electricity offered designers a new playground. Independent artists such as Marinot, Navarre and Heiligenstein explored art for art’s sake, creating some unique, sought-after pieces which prefigure the Studio Glass movement.

Sweden, the Netherlands and Italy trod their own path, developing some original trends, while France pursued the remarkable tradition of pâte de verre.

René Lalique

Art for the masses…

By concentrating on producing beautiful utilitarian objects at a lower cost using mass production techniques, René Lalique (1860-1945) embodied the alliance between art and industry in every area of modern life, from sculpture to architecture, from tableware to light fittings, perfumery to jewellery and motor cars to ocean liners.

.

The Verreries du Centre

The Centre region (La Louvière, Manage, etc.) was the jewel in Belgium’s household glassmaking industry, although it did not exactly stand out from the crowd for its artistic output until the Scailmont glassworks invited Frenchman Charles Catteau to supply some projects in the taste of the day. As artistic director at the Boch Keramis pottery, and a keen supporter of Art Deco, which he taught at the Ecole Industrielle in La Louvière, Catteau would prove an inspirational figure.

The items produced during this period are easily as good as the creations coming out of Val Saint-Lambert.

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF GLASS: ARTISTIC AUTONOMY

With the confirmation of the essential role played by the designers, we see in the inter-war years the two major trends which would develop after the Second World War.

The first consisted in making use of the talent of the designers within the industry itself, via the creative departments and studios while not overlooking the imperatives inherent in the businesses. The close collaborations which evolved would lead in the fifties to the triumph of Design.

As an individual process, the second had nothing to do with the purposes of a private business, regardless of the relationships that it might have with it. For artists such as Maurice Marinot and his followers, the main thing was to express themselves ‘in glass’, a trend which in the 1970s paved the way for the arrival on the scene of a material which bore an industrial label but had the status of an artistic medium in its own right.

Design

At the Cristalleries du Val Saint-Lambert, since the period of Art Nouveau, which saw plenty of external collaborations, the creative drive lay almost exclusively with the internal design service. As from the 1960s, the Val gradually opened up to outside artists, both Belgian and foreign, actively encouraging them – whether they were trained glassworkers or not – to express themselves in glass. The first collaboration took place in 1961, with artist/designer Charles Conrad, who was born in Antwerp in 1912. Other celebrated artists, such as René Delvenne, Nanny Still, Samuel Herman and Harvey Littleton, pursued the artistic impetus that was a feature of Studio Glass within Val Saint-Lambert.

Workshop creation

In 1962, ceramic artist Harvey Littleton caused a sensation by proving that hot glass is a discipline that is accessible outside the factory floor: this was the start of the international Studio Glass movement.

As it spread throughout Europe, this American model tapped into independent initiatives by some great pioneers, including Erwin Eisch, while Czech artists, led by Stanislav Libensky, capitalised on support from industry, which allowed them to explore monumental sculpture.

Contemporary artistic creation

In contemporary art, glass is present in various different ways. There are almost as many trends as there are creators, each using his or her own conception of the art, method and technique. Even though working with glass demands very sophisticated craftsmanship, all the glassmakers want to be considered as artists rather than artist-decorators or craftsmen, and all are pursuing the path which has seen the split between the ‘medium’ of glass and the label of being an industrial material which it was saddled with.